Press release: May 2, 2017

School tuck shops are losing ground to home-packed lunches, according to latest results from the long-running CensusatSchool TataurangaKiteKura. In the past 10 years, the percentage of students buying lunches from tuck shops has halved.

Overall, 86% of primary and secondary school students brought their lunch from home on the day they responded to the survey, with just 5% buying from the tuck shop. When the same question was asked a decade ago, 79% were bringing lunch from home and 10% buying at their school’s tuck shop.

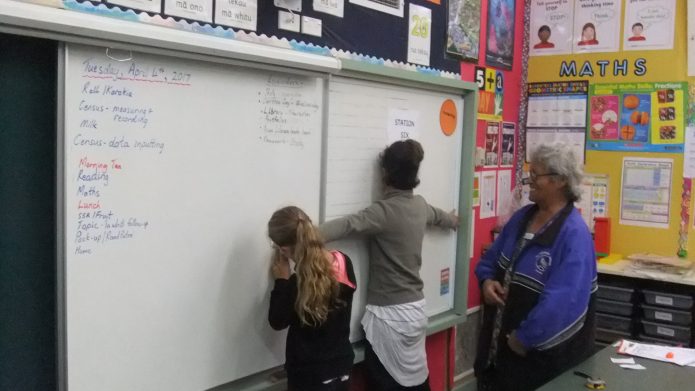

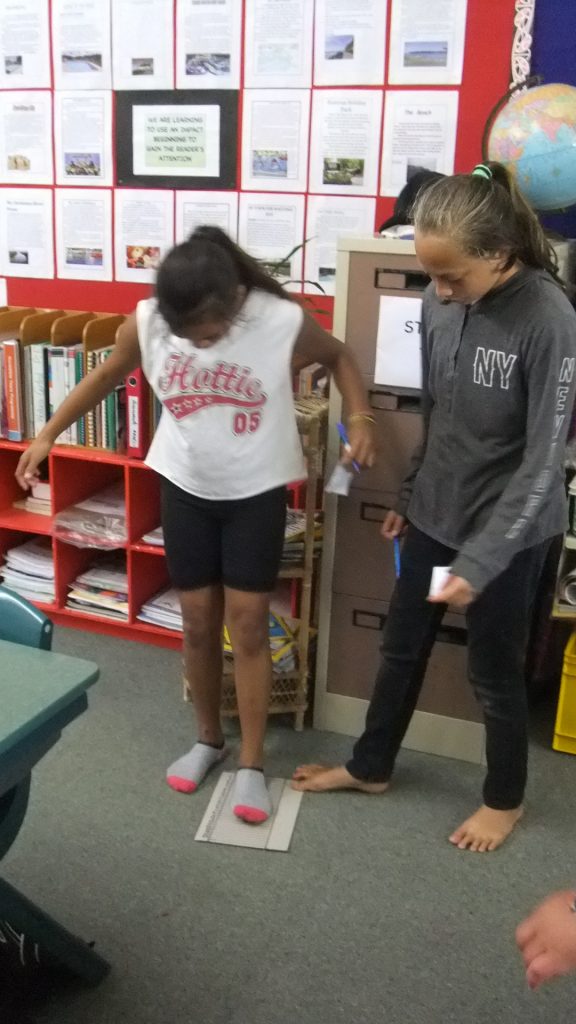

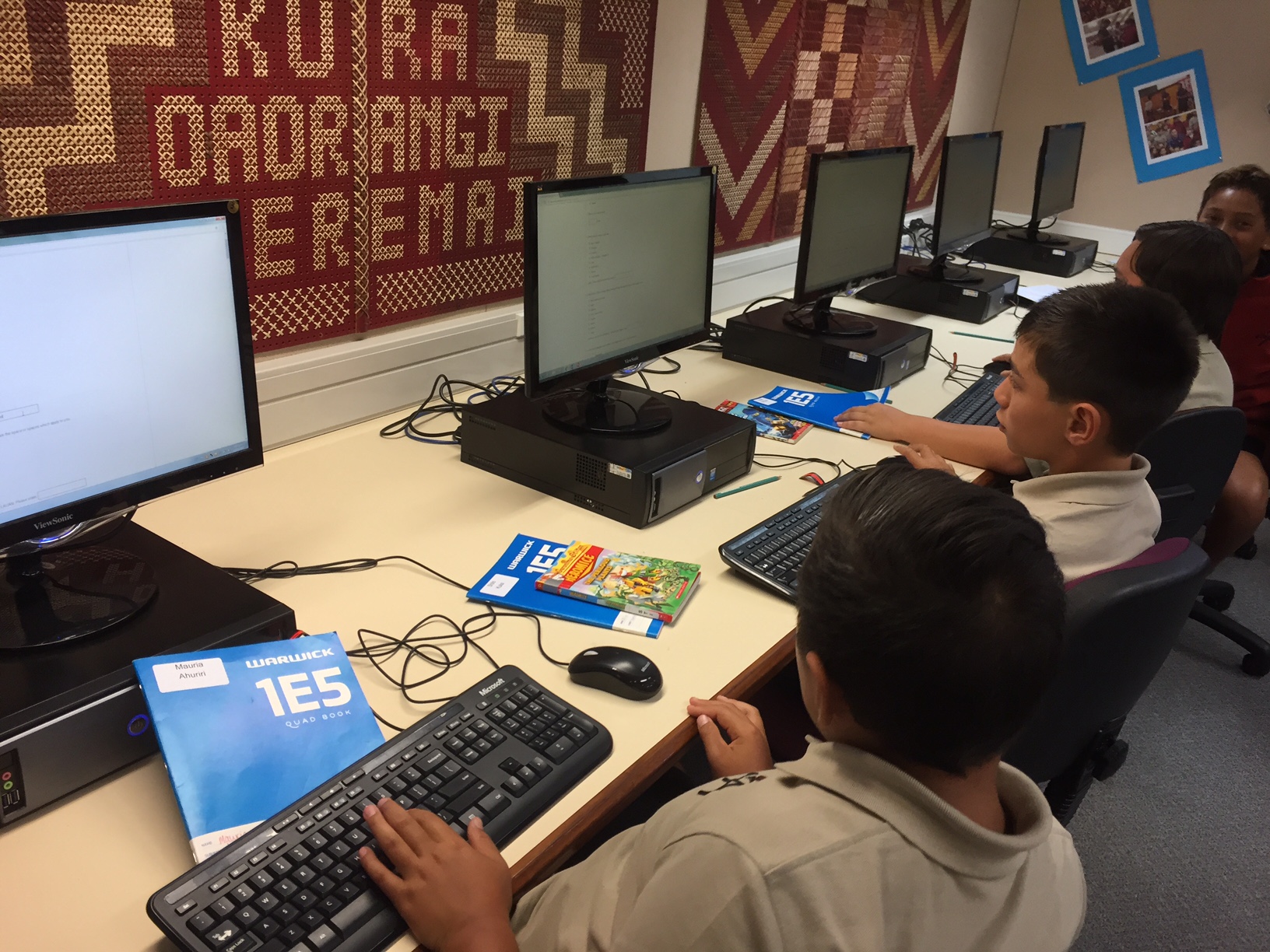

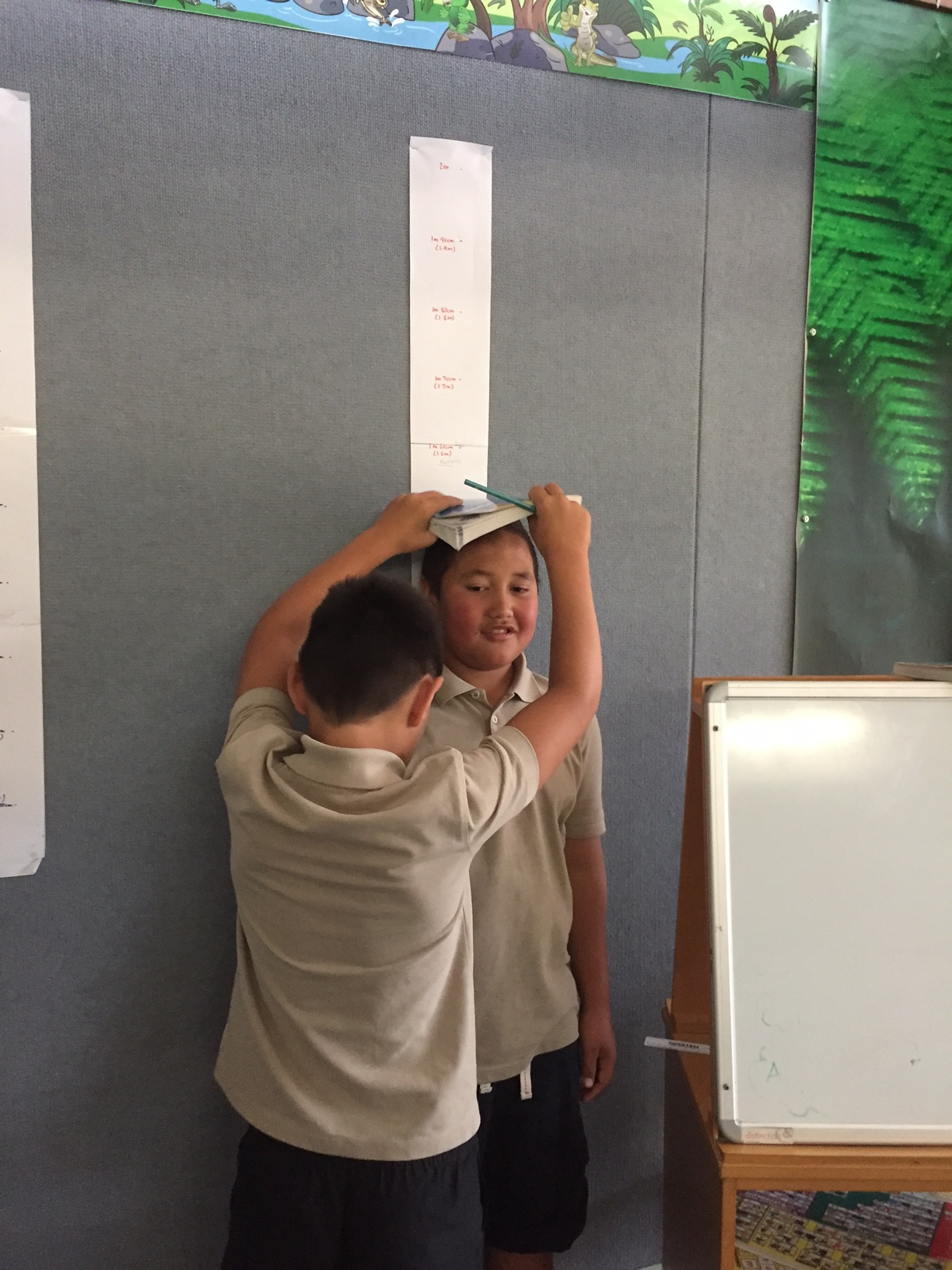

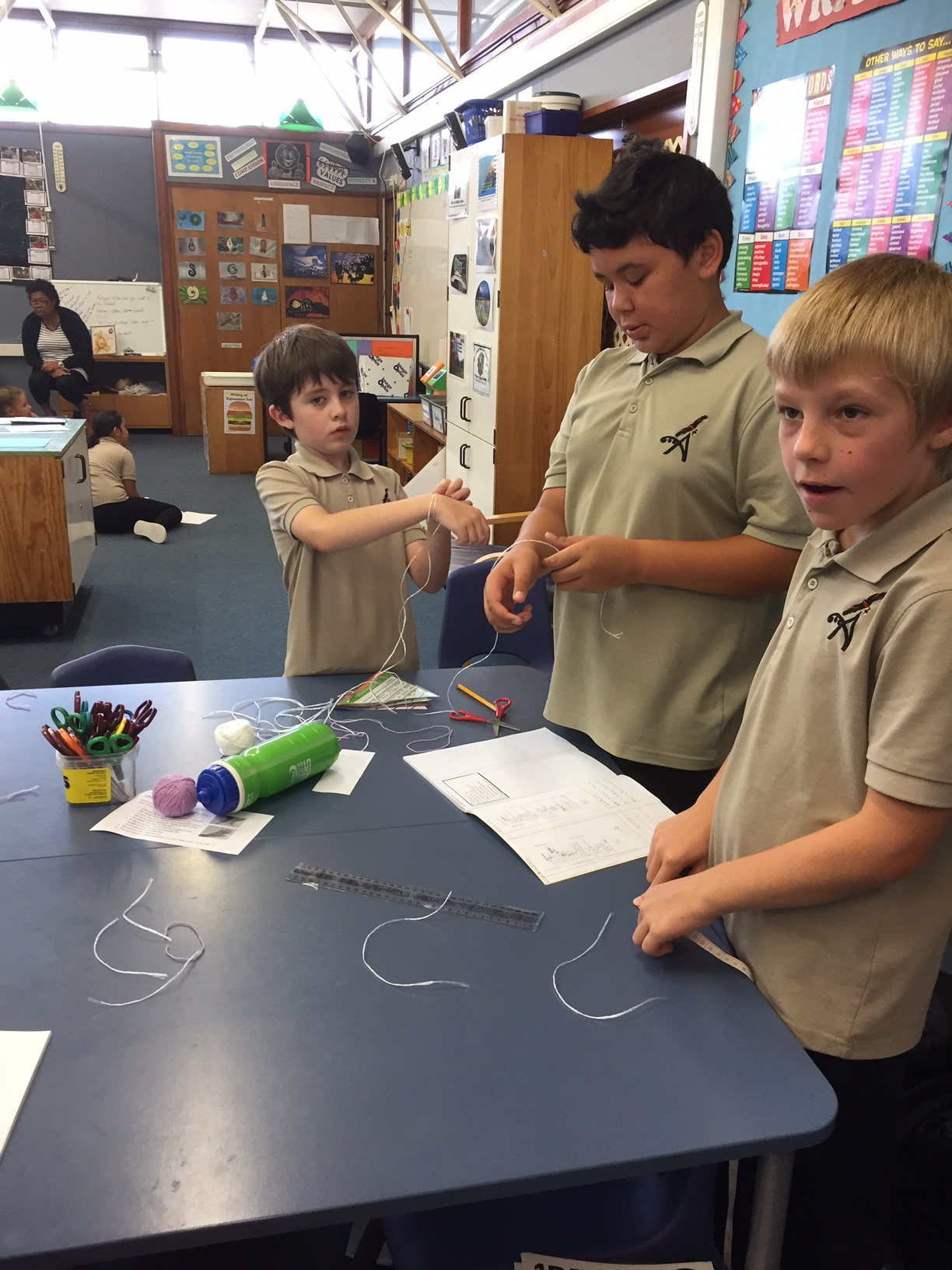

CensusAtSchool TataurangaKiTeKura is a national, biennial project run by the University of Auckland’s Department of Statistics that shows children the relevance of statistics to everyday life. In class, Year 5 to Year 13 students (aged 9 to 18) use digital devices to answer 35 online questions in English or te reo Māori, providing a unique snapshot of Kiwi childhoods. So far, more than 10,000 students have taken part, and they have answered several questions on food.

The Census asked “Where did you get your lunch from today?” with the possible answers “home” (overall 86%; primary 93%; high school 78%); “a shop on the way to school” (overall 3%; primary 2%; high school 3%); “the school shop” (overall 5%; primary 3%; high school 7%); “a friend at school” (overall 0.5%; primary 0.2%; high school 1%); “provided by my school” (overall 2%; primary 1%; high school 4%); and “don’t have any” (overall 3.6%; primary 1%; high school 7%).

The backdrop is growing childhood obesity and much public debate over what kids should be eating at school. An Education Review Office report released just before Easter found that most schools were doing a good job equipping young people to make good food choices, but acknowledged that factors such as family finances and attitudes, student price sensitivity and takeaway shops near schools could prevent children bringing or choosing good-quality lunches. Many school-run tuck shops lost money, so schools often contracted out to providers who “were profit-driven, and tended to be most interested in stocking what would sell well; not usually the healthy options”.

CensusAtSchool co-director Rachel Cunliffe, who has two school-aged children, says that she wonders if public discussions have raised parents’ awareness of the importance of the school lunches they provide, and that this has led to more concerted efforts to provide packed lunches. Mrs Cunliffe makes her two primary school-aged children daily packed lunches, and once a term they are allowed to buy lunch at school: “Of course, they tell me that everyone else gets to buy their lunches all the time.”

The past few years has also brought publicity about some school children going without breakfast or lunch, and Mrs Cunliffe says she was “relieved” that the number of children reporting that they had no lunch was fewer than expected. “That said, you don’t want to think that any students are going hungry,” she says. “I am hoping that the 7% of high-school students not having any lunch is because they didn’t get their act together to prepare it. A packed lunch does take some forethought and preparation.”

The Census also asked children who brought packed lunches how many items grown at home were among the food provided that day. A quarter said they had at least one home-grown item in their lunchbox.

This year’s edition of CensusAtSchool TataurangaKiteKura started on February 7. Teachers can register their classes and take part at any time before it finishes on July 7. The Census is part of an international effort to boost statistical capability among young people, and is carried out in Australia, the United Kingdom, Canada, the United States, Japan and South Africa.

The countries share some questions so comparisons can be made. In New Zealand, the Census started 2003, and is run by the University of Auckland’s Department of Statistics with support from Statistics NZ and the Ministry of Education.